We’re probably painfully aware that the change we seek takes time. But we’ve also been told that as long as we continue to practice our new habits, they’ll eventually stick. By then, we would’ve adapted to the change we strove for.

Great! Finally, a simple path to excelling.

Well, not exactly. In sports, I often come across “practice players”. These are the athletes who excel during individual practice or isolated skill training, but struggle to put it together once competition starts. No, I’m not trying to insult these players – just hear me out. These could be players who are knockdown shooters in basketball – can’t miss a single shot during practice, but fail to deliver anything close to their usual level of performance in competition.

It’s especially frustrating for these athletes, since they know they’re capable of producing results. Just not when it matters.

If the road to change is so simple, why do so-called practice players struggle? What actually happens behind the scenes when we’re developing our technique?

What is skill acquisition?

Let’s get technical for a moment. Skill acquisition, also referred to as motor learning and control, is the interdisciplinary science of intention, perception, action, and calibration of the performer-environment relationship.

What does that mean for us?

In simplified terms, skill acquisition refers to voluntary control over the movements of joints and body segments in an effort to solve a motor skill problem and achieve a task goal.

We start with a goal: let’s say, something simple like opening a door.

To achieve this task goal, the body has to reproduce a series of steps such as lifting a hand to grab the handle, twisting or pulling the handle, and finally pushing or pulling the door.

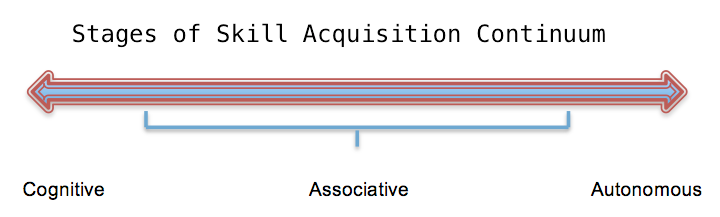

Fitts and Posner (1967) - Three-stage continuum of practice model

First stage: cognitive

In this first cognitive stage of skill acquisition, we have to consciously think of each step: make sure to unlock the door first before opening it, push instead of pull, and etc.

Errors may occur too. You insert the key but always turn the wrong way. You often get things wrong, but that’s okay since you’re making a lot of progress.

It’s probably unrealistic to ask you to remember the first time you opened a door, but it probably didn’t go as smoothly as your door-opening experience this morning (unless you were half awake and stubbed your toe against it - in which case, my condolences).

In the process of acquiring a skill, we, through practice and assimilation, refine and make automatic the desired movement.

Second stage: associative

As we continue to repeat this task, our bodies adapt - we get better at it. We start to not have to think about it. We step into the second stage - associative.

In the second stage, we’re familiar enough with the skill that we can start introducing flexibility. Also known as: the real world.

In the real world, doors come in all shapes and sizes. There are key locks, code locks, even fingerprint and facial sensors now. There are also sliding doors, which I often get on my 3rd try after pushing then pulling (who can relate?).

Given the variability of the real world, we start noticing the environmental feedback and start to experiment with adjusting our approach. If our hands are occupied, can we open the door with our feet?

Third stage: autonomous

This is the final stage of skill acquisition. We’re finally able to perform the skill effectively and efficiently without much thought. We can multitask and complete the task without sparing any mental capacity.

This is also where our skills usually plateau. And that’s ok. Unless we’re lock-pickers, we’re usually content with our average ability to open doors.

So we ask: how is all this relevant?

Opening a door is a relatively simple skill with little variations to the movement. Doors may come in varying sizes and shapes, but they will generally work the same way.

The skills we aim to acquire and the goals we set for ourselves are usually much harder.

Mastering the cognitive stage is only the first step. How well we use it, and when and where we choose to use it are the important steps to actually build a skill that would solve our problems or reach a designated goal.

Practiced but not adapted:

Let’s revisit our practice player. Now that we know more about the skill acquisition model, we have a better idea of why they can’t convert in game when they’ve clearly shown that they have the technique. I’d suggest that perhaps a larger emphasis of training has to be placed on the diversification of the movement pattern.

What does that mean?

No two movement patterns will ever be the same; we are constantly outputting close imitations of what we believe is the closest, most efficient version of the motor pattern that we have acquired. Continuing with the basketball analogy – yes, we’re shooting the ball with the same form, but:

the distance from the rim varies

how we catch the ball varies

how we’re defended varies

how we’re moving when we catch the ball varies (speed, direction, leg placement etc.)

So on and so forth

So yes, we’re still shooting the ball, but with so many differences leading up to the movement, it may as well be another skill entirely. Only when one can flexibly execute the same skill under varying circumstances can one be called a master at it.

Photo by J. Meric on Getty Images

A great example of someone who has a high mastery of adaptability is the now-retired NBA sharpshooter JJ Redick. JJ Redick has had an exceptional 15-year NBA career as one of the best pure shooters in the league. When speaking about his approach to shooting, many of his peers have been amazed by his ability to shake his defender, sprint to a spot, and catch and shoot the basketball from any direction. This comes from his “psychotic” attention to detail, and his willingness to practice for any scenario he can think of.

Every single spot shot I shoot...I would change up my footwork...just so I can teach my brain to habitually and naturally do my footwork differently every time […]. So when I’m forced to do so in a game, I can execute it without having to think about it.” By doing so, JJ builds not only muscle memory, but also high variability in his approach while still reaching the same goal of shooting the ball.

Realistically, one can be a master at their craft, but true mastery of a skill is an oxymoron, especially when considering what we now know about acquiring a skill via the skill acquisition model. Even the best of the best, Stephen Curry, has only shot 42.6% from the 3 point range over his career. Don’t get me wrong, 42.6% is a legendary statistic, but it just means that even the best shooter in the history of the NBA misses 57.4% of the time in game.

Practicing healthy eating: the associative stage

We can take these lessons we have learnt in skill acquisition and apply them to our health goals as well.

Take dieting or drinking for example. We might be disciplined when we’re cooking for ourselves at home, but make all the wrong choices once we eat out. That’s the equivalent of a practice player: a person who can only thrive in a controlled environment. We fail to execute the skills we have acquired once uncertainty is introduced.

Perhaps, like JJ Redick, we should also map out the scenarios we struggle with, thrive in, or will inevitably get put in, and practice them.

This takes planning. For example:

If you know you’re likely to snack between lunch and dinner, plan ahead by packing a healthy snack

If you’re eating out, narrow down the healthy options and pick from those

If the restaurant has already been booked, you can always take a look at the menu in advance to make more informed choices

If your friends are planning to go drinking afterwards, pre-plan a non-alcoholic drink of your choice (or a reason to skip the alcohol entirely)

You can’t completely plan for the endless amount of scenarios that may occur. Even Steph Curry misses when faced with variability. But you can practice for the ones that you expect to come. That’s how we adapt, improve, and open the door to autonomy.

That being said, if you're feeling the love and would like to make a kind donation to fuel my rather large amount of caffeine intake, you can buy me a coffee here.

My content here is free, so a donation of any amount would mean the world to me as it gives me the confidence that what I’m doing is making a difference!

Insightful connection between forming a skill and healthy eating – I’ve never thought about “practicing” eating habits in non-controlled settings but it makes so much sense. Skill level up!